The Product Requirements Document or PRD describes all aspects of a new idea required or desired to make its realization a success. The PRD is the bridge between the often vague project briefing and the highly detailed engineering implementation plan. It is also known as the Program Of Requirements (POR), Design Specification, or Product Nucleus in some circles.

The PRD provides designers and developers with a realistic sense of what is required in the product in terms of what it should look and feel like, how it should function, how it should carry out the brand and help the business, and in which ways it should be used.

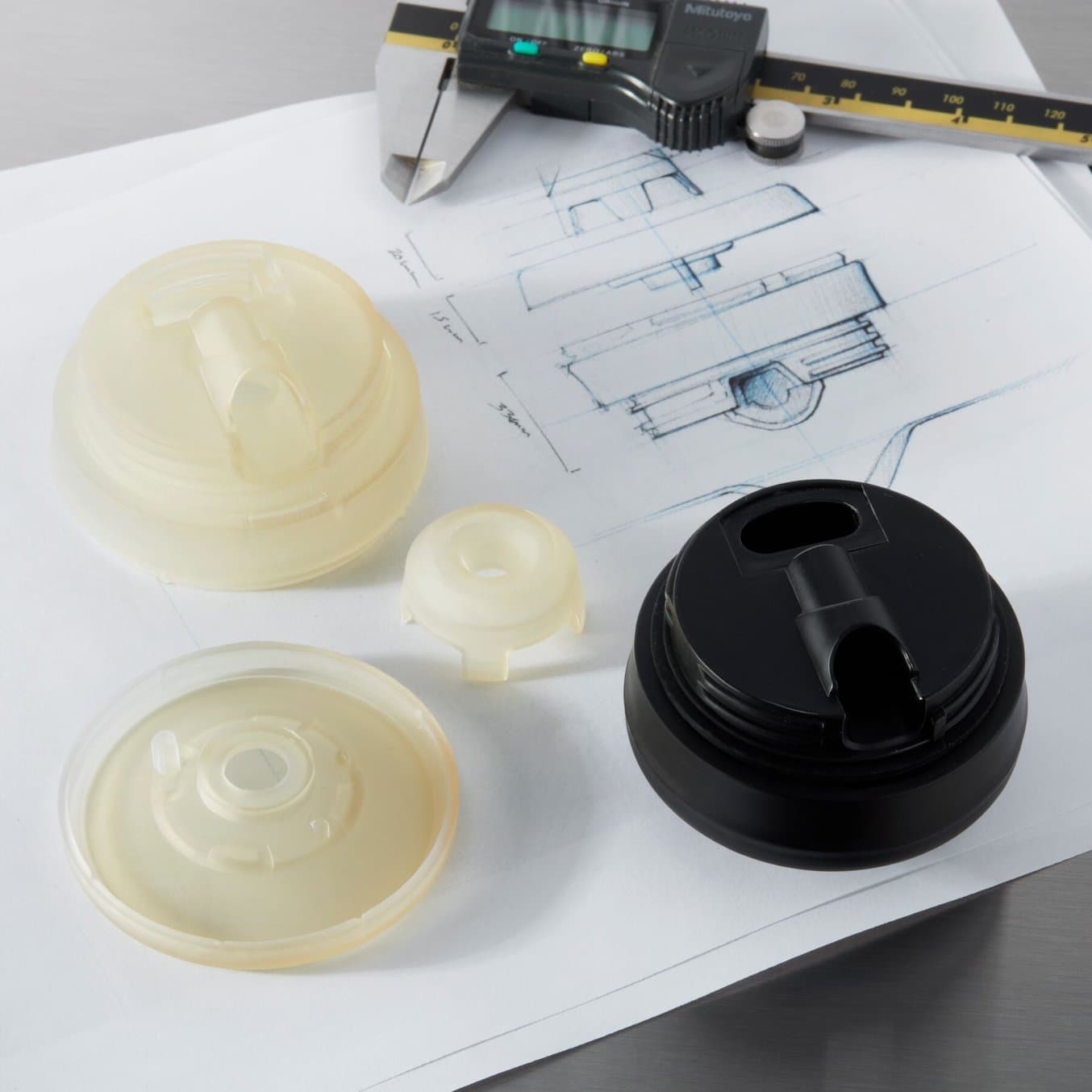

Guide to Rapid Prototyping for Product Development

In this guide, you’ll learn how rapid prototyping fits into the product development process, its applications, and what rapid prototyping tools are available to today’s product development teams.

Book a Free Consultation

Get in touch with our 3D printing experts for a 1:1 consultation to find the right solution for your business, receive ROI analyses, test prints, and more.

How the PRD Works

Someone in the company has a big idea for a new product and wants to start development. They outline the generic concept of the vision in a project briefing, hands it out to the design department, and off they go, right? Wrong. In reality, designs often get produced that perform well in one or a few areas, but miss the mark in others. This is because even though on an implicit level they feel they have understood the vision of the initiator and got enthusiastic to commence development, the outcome will more often than not prove that the interpreted concept was not the intended one.

Yet, some things in product development are simple enough not to require a PRD. ‘Design a single-piece injection-molded one-liter watering can with a geometrical aesthetic to be an eye-catcher in minimalist home interiors,’ and ‘Design an inflatable donut for beachgoers that can hold a 200-pound person afloat’ are sufficient for an initial PRD for those items, together with a description of the target user and a moodboard perhaps.

Some products are simple enough not to require a PRD, but it is indispensable for more complex products. Scroll down to download our real-life PRD example of the Apple Airpods Pro.

But when functionality and hardware configuration get more complicated, it is paramount that descriptions get more specific. For example, developing a mass-manufactured biocomposite birdhouse is already a level up. Different aperture sizes will attract different species. There is the proper amount of ventilation, temperature regulation, protection, and that is just the start of the list. Designers will need to be very well informed in order to come up with a successful design.

With complex integrated products, many different aspects come into play to meet their own set of requirements. There is hardware, software, electronics, user experience, assembly, branding and labeling, packaging, interoperability, service policy—the list goes on. These components are hardly ever well-understood by the development team, and properly capturing all of them will at least result in a five-page document.

So if your soon-to-be-launched product or system cannot comprehensively be described in a single paragraph, it is a prerequisite that it has a PRD attached to it.

How to Choose a 3D Printing Technology

Having trouble finding the best 3D printing technology for your needs? In this video guide, we compare FDM, SLA, and SLS technologies across popular buying considerations.

Pros and Cons of a PRD

Besides guaranteeing a successful translation of the project originator’s vision to a tangible product, there are multiple advantages to setting up a PRD:

-

It evaluates and spots future obstacles

-

It helps establish evaluation criteria for the success of new products

-

It conveys the priority of the product’s different aspects

-

It instills awareness of the various customers and use case scenarios

-

It firmly roots the role of product management into new development processes

-

It ties product development to a comprehensive vision rather than just being a series of feature additions and improvements

-

It ensures the soundness of the design

-

It provides a full overview of the project which will help everyone to tell and sell its story

-

It improves multidisciplinary teamwork and comprehensive mutual understanding

-

It relieves the stress of the unknown by making the project comprehensible for those involved which uplifts the spirit and gets people in gear

The disadvantages of setting up a PRD are:

-

Writing a PRD is an acquired skill that takes time to attain;

-

Highly specific requirements too early in the process can evoke discussions that turn out time-consuming and ineffective

-

A too vague and long-winded PRD confuses everyone involved and tends to get ignored

-

-

It can prevent face-to-face conversations where the right questions are asked to help shed light on the design’s preferred tacit qualities: ‘if it meets all the requirements, it must be what the client wants!’

-

It can impede design explorations of a more open kind that may lead to different kinds of successful products, besides the one specified.

How to Write a Successful PRD

A PRD is first and foremost a broadly scoped outline for the development trajectory that makes the requirements explicit from the perspectives of different stakeholders, product aspects, and processes involved. User testing of current products, user surveys as well as observational studies but also design explorations, technological developments, new business strategies, socio-cultural trends, repair and maintenance, a changing environment, new production processes such as digital fabrication, logistics, packaging, legislative regulations, anthropometry data, and literature are all viable sources to generate requirements for upcoming products. If a design meets all the various requirements in the PRD, it has a strong chance of being a good design. Therefore, all the requirements together have to exhaustively cover the project’s objectives. A PRD with generic requirements that cover all areas is still better than an incomplete PRD with lots of details.

To provide a complete picture and create realistic requirements, it is good practice to mentally rehearse the life cycle for this specific product, from manufacturing to distribution, including in-use scenarios and end-of-life. Before finalizing your PRD, make sure to check that you haven’t forgotten certain aspects that may lead designers into unwanted directions, and vice versa, that you haven’t included requirements so detailed that they exclude possible alternative concepts that may lead to a successful design as well. Remember that writing a PRD is already part of design thinking itself.

A second key aspect of a PRD is prioritization. Designers and engineers need to know what to focus on to create a successful product. A PRD is not a set-in-stone dictate of what a product should be; it is the start of the social process called design, and to varying extents, there is room for negotiation. That is why adaptations will always be made to the PRD during the development process, making it, in essence, a living document.

A good way to convey prioritization is using a triage; divide all requirements into must-haves, want-to-haves, and nice-to-haves. This way, designers and engineers know that without meeting the must-haves, the product will never even come to fruition. And without meeting at least a few want-to-haves, they may create a minimum viable product, but customers and product managers alike may not like it. The nice-to-haves are extras that will be developed in case of extra available resources.

The orange acrylic cover of Formlabs stereolithography 3D printers is a must-have because it is part of the brand’s heritage and it blocks UV light that would interfere with the process.

An even better way to assign priority is by assigning a more detailed scale, since some must-haves are still more important than others and some nice-to-haves are more called-for by customers than others. A new Formlabs stereolithography 3D printer must come with an orange acrylic cover because it is part of the brand’s heritage and it blocks UV light that would interfere with the process, but maybe the hard requirement of touchscreen interaction for print settings is negotiable if a designer can find another elegant and feasible solution that matches all scenarios-of-use. The material run-out sensor as a nice-to-have may add more benefit than the LED-backlit logo on the face of the machine. Assigning a priority number, say on a scale from 1 to 10, to the different requirements also aids in concept selection as it makes it possible to calculate a success score for each concept, for example, through the Quality Function Deployment method or other types of decision matrices.

A third key requirement for a PRD is that it makes development goals specific. Use clearly written complete sentences and specify physical quantities wherever possible. It is best practice to make use of the SMART-principle; goals have to be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. Where possible, show how the different product features will contribute to the success metrics of your business. This way of formulating requirements also helps to make product managers aware of irrelevant goals or constraints that may not be grounded in the territory of the design problem, for example out of habit, misunderstanding, or conformity.

Fourth, keep the PRD concise. It is not a ready-made technical implementation plan; engineers will create those internally to their department. A good PRD will refer to the required behavior of the product in its contexts-of-use rather than fully defining the design beforehand using detailed specifications, even if it will in most cases contain some of those as well. The realization, then, is up to the design experts.

A PRD is also not a collection of expressions that different stakeholders have stated about the intended design. These often contain statements that boil down to the same thing and can be more accurately captured by a well-written requirement. It is good practice to explicitly check for redundancies across the different requirements and see if they can be combined.

A PRD is most of all an overview of product features, an explanation of how they contribute to the success for different stakeholders, and a demonstration of how they will play out in different use cases. In its most compact form, an initial PRD is nothing more than a shortlist of key requirements that may grow longer and more accurate over time to reflect the evolution of design decisions.

It is common practice for independent designers and creative studios to set up a two-page questionnaire towards their clients that asks them to create the equivalent of such a shortlist. This gives the designer more than, say, a 15-minute briefing to go by, since it will ask for necessary specifics such as the nature of the design project within the client’s company, envisioned functionality and interaction, the target demographic, unique benefits over the competition, design language preferences, deliverables, deadlines, and budget. For complex design projects, developers will then expand upon the shortlist towards a more full-blown PRD. The ultimate goal is that everyone arrives at a shared understanding of what the project is about.

The Structure of a PRD

A PRD typically starts with a title page that contains general information such as the project name/code, company and division, responsible manager, date of creation, and version of the document. The introduction then sets out the context of the project and describes why the new product needs to be developed in terms of needs experienced by different groups of people towards a desired future situation involving the new product.

The body of the PRD begins with a description of the project’s objectives. This includes the overall vision for the product and high-level goals for the company paired with success metrics, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), and a timeframe wherever possible.

The PRD then goes on to describe the sources of the requirements: the stakeholders and their role in the product life cycle (PLC), as well as use cases demonstrating the envisioned use of the product’s key features by real people in real situations.

The requirements themselves are best grouped under the product’s different aspects because this is the most complete way of listing them. Different stakeholders and use cases may bring up overlapping or identical requirements. At the same time, a clear categorization of the product’s aspects in areas such as hardware, technological functionality, interactivity, software, aesthetics and customization, manufacturing, and regulations results in a list that thoroughly covers all the points. Make sure to number each category and every individual requirement, as shown in this snippet of a PRD for custom earbuds:

5 Customization

5.1 The product shall offer multiple custom fit options that provide an ideal fit to at least 98% of the general population. (P10)

5.2 The product shall offer customization so that it does not fall out of the ear once during running a 10-kilometer route by runners of different heights, ethnicities, and sexes. (P9)

5.3 The product shall be offered with an additional engraving service for texts or icons onto the product. (P3)

5.4 The product shall be offered in at least five colorways including black, white, gold, and a selection of our successful colorways that include Pine Green, Khaki, Cactus, Seafoam, Coastal Grey, Alaskan blue, and Stone for our wearables. (P5)

In our example, the P-code after each requirement indicates its priority on a scale from 1 to 10, 10 being the most important.

The PRD also includes topics that need further research in order to be able to complete the document. These are the unknown factors not yet decided upon that may drive product development in new directions at the time they are answered. A company may, for example, want to perform research into new materials like high-performance resins that open up new markets and design opportunities, such as 3D printed insoles for shoes.

The PRD should not limit design possibilities. Some topics might require further research in order to be able to complete the document, for example, the new materials that enabled these 3D printed insoles for New Balance shoes.

To conclude, the PRD should contain milestones related to planned dates for concept presentations, ‘design freeze’ moments where fixed decisions are made about the entire design or important aspects of it, as well as its planned manufacturing, shipping, and release dates. Lastly, make sure to provide a list of resources and information repositories for designers to refer to during the design process, a glossary explaining technical terms present in the document, optional appendices with detailed information, an overview of competing products including the new product’s positioning, supporting sketches or mockups with initial ideas, and component drawings explaining the required internal dimensions and functional configuration.

In short, the structure of a PRD looks like this:

-

Title section

-

Project title and/or code

-

Responsible manager(s)

-

Date of creation

-

Document version

-

-

Introduction

-

Background Information / Context

-

Problem Definition / User Needs

-

-

Objectives

-

Vision

-

Goals

-

Product Positioning

-

-

Stakeholders

-

Users

-

Purchasers

-

Manufacturers

-

Customer Service

-

Marketing & Sales

-

External Partners

-

Regulatory Instances

-

Retailers

-

Etc…

-

-

Use Cases

-

User Story #1

-

User Story #2

-

Etc…

-

-

Aspects

-

Hardware

-

Software

-

Design

-

User Experience

-

Interactivity

-

Customization

-

Manufacturing

-

Regulations

-

Etc…

-

-

Open Questions / Future Work

-

Milestones

-

Resources

-

Appendices

-

Glossary / Explanation of Terms

PRD Template and Example (Free Download)

Of course, it’s always helpful to look at a real-life example and not just an empty outline, so we created a faux PRD for a well-known product. Our PRD example describes the requirements for the Apple AirPods Pro at the time the project started and only the first generation AirPods were on the market.

Rather than creating a PRD from scratch, you can use this template as the starting point when you create a PRD for your product. Just click on “Use Template” in the top right corner to duplicate it, delete any unnecessary info, and modify the document structure according to your needs.

Note that while the PRD is largely based on actual data pertaining to the product as well as existing consumer electronics regulations, as a corporate document, it is entirely fictive.

Summary

The Product Requirements Document (PRD) is an essential tool for the design and product development process, much like the 3D printers that enable prototyping and iterating on new designs rapidly.

Setting up requirements is an expertise in itself. They have to cover all areas without redundancy or incompleteness, be written in unambiguous language, and convey priorities in terms of must-haves, want-to-haves, and nice-to-haves avoiding direct technical specifications related to the design that unnecessarily limit possibilities. A thorough PRD also provides additional information such as external resources, product positioning tables, sketches, or mockups demonstrating the vision, and technical components to be integrated into the design.

Not sure which 3D printing solution fits your business best? Book a 1:1 consultation to compare options, evaluate ROI, try out test prints, and more.