In our guide to stereolithography, we cover a brief history of the process, as well as an in-depth look at how this 3D printing method works. But what does this all mean for where stereolithography (SLA) is now, and where this technology (and 3D printing more generally) is going?

In this post, we’ll explore the origins of SLA, some key points in its evolution, and the current status of this technology, with some archival videos along the way.

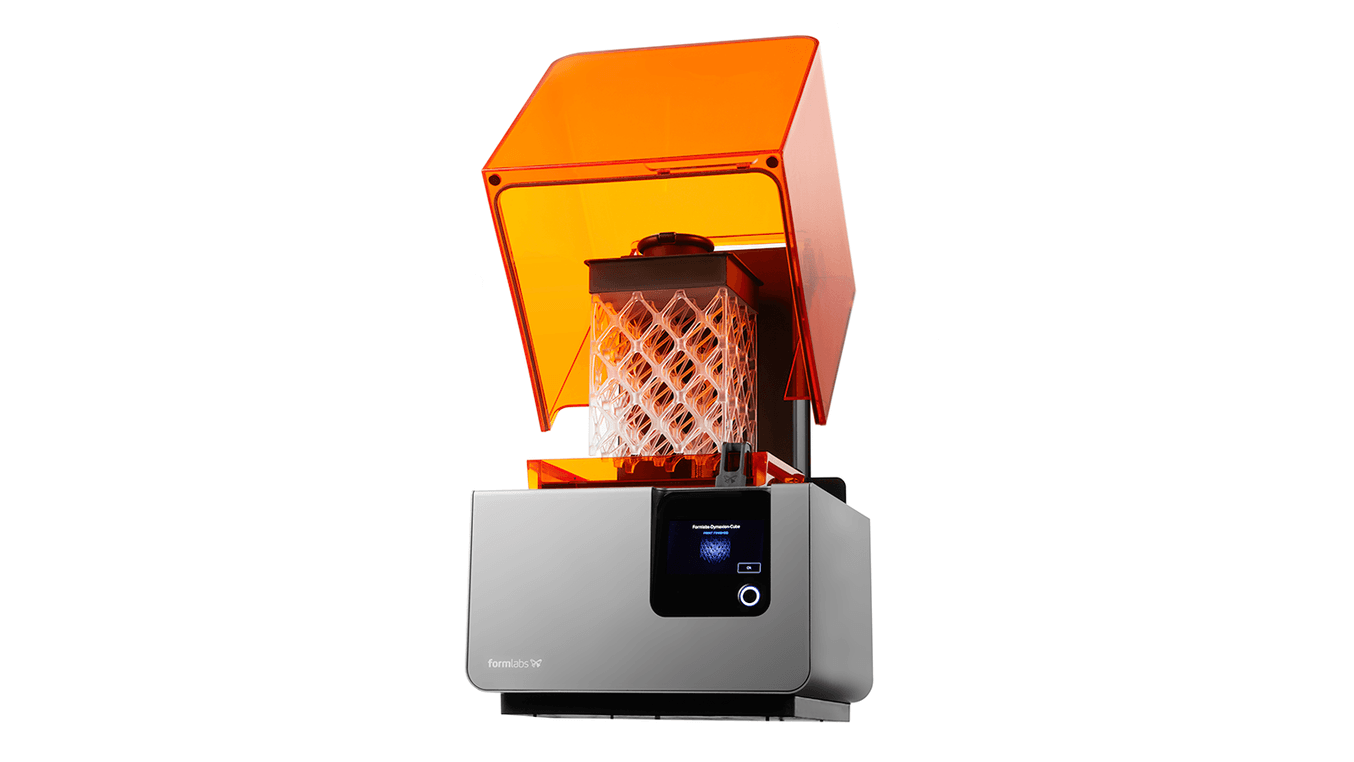

We're celebrating 25 million successful parts printed on our desktop stereolithography 3D printer, the Form 2! Learn more about reliable, intuitive 3D printing at a fraction of the cost and footprint of industrial 3D printers.

Inventing the First 3D Printing Method

While fused deposition modeling (FDM), where melted plastic is extruded from a nozzle to form a part, is probably the best known 3D printing process today, SLA was the first method invented.

stereolithography /sterē-ōliˈTHäɡrəfē/: a 3D printing process by which a laser cures a liquid photopolymer resin to form a three-dimensional object from a digital file.

Amidst similar emerging inventions from Japanese researcher Dr. Hideo Kodama and French inventors Alain Le Mehaute, Olivier de Witte and Jean Claude André, Charles (Chuck) W. Hull coined the term “stereolithography” and patented the technology in 1984, then founded 3D Systems to commercialize it, releasing the SLA-1 machine in 1987.

In an early video, Chuck Hull of 3D Systems explains stereolithography.

Entering Mainstream Consciousness

Long before the RepRap movement, Makerbot, and the advent of FDM 3D printing in the late 2000s, SLA was making waves. As large companies adopted this new technology for rapid prototyping, it trickled into mainstream media–for example, this clip from Good Morning America was aired in 1989:

“It seems like magic, but it’s called stereolithography.” A Good Morning America segment from 1989 explores 3D printing.

As SLA worked its way into more businesses, Invisalign dental aligners became the highest volume use case, producing over 40,000 molds a day using stereolithography printers. Custom aligners, with a high level of value and high degree of customization, were a perfect test bed for this nascent technology, even before machines reduced significantly in cost.

While desktop 3D printing was making waves, 3D printing in professional, industrial settings continued to grow steadily, including stereolithography. In 2013, 3D printing in the context of manufacturing even made its way into former U.S. President Barack Obama’s State of the Union address.

“A once shuttered warehouse is now a state-of-the-art lab where workers are mastering the 3D printing that has the potential to revolutionize the way we make almost everything.” Barack Obama, 2013 (0:37)

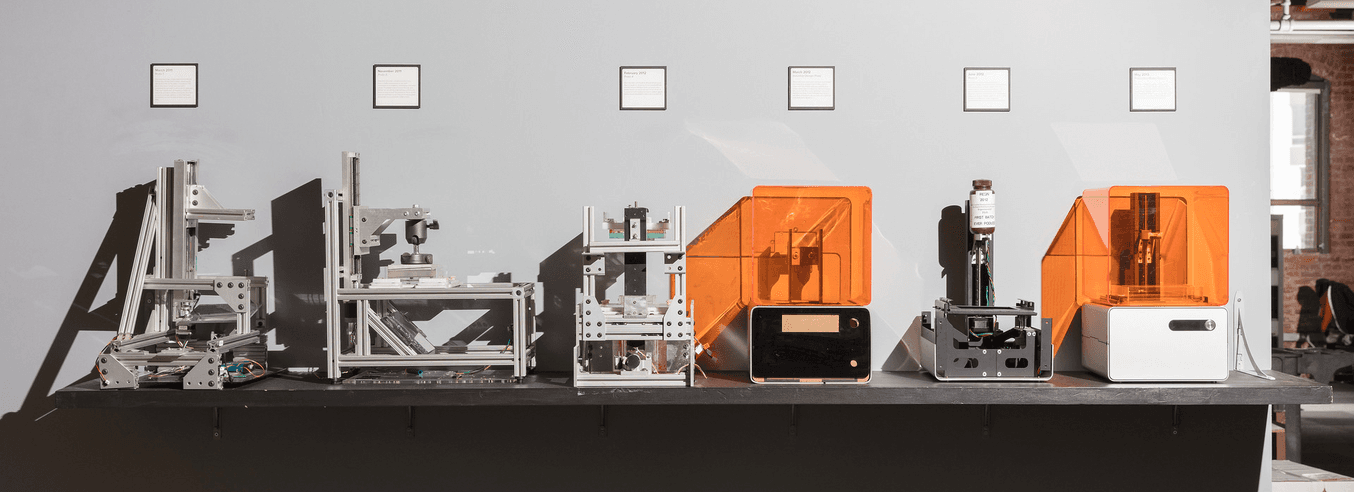

Bringing Stereolithography to the Desktop

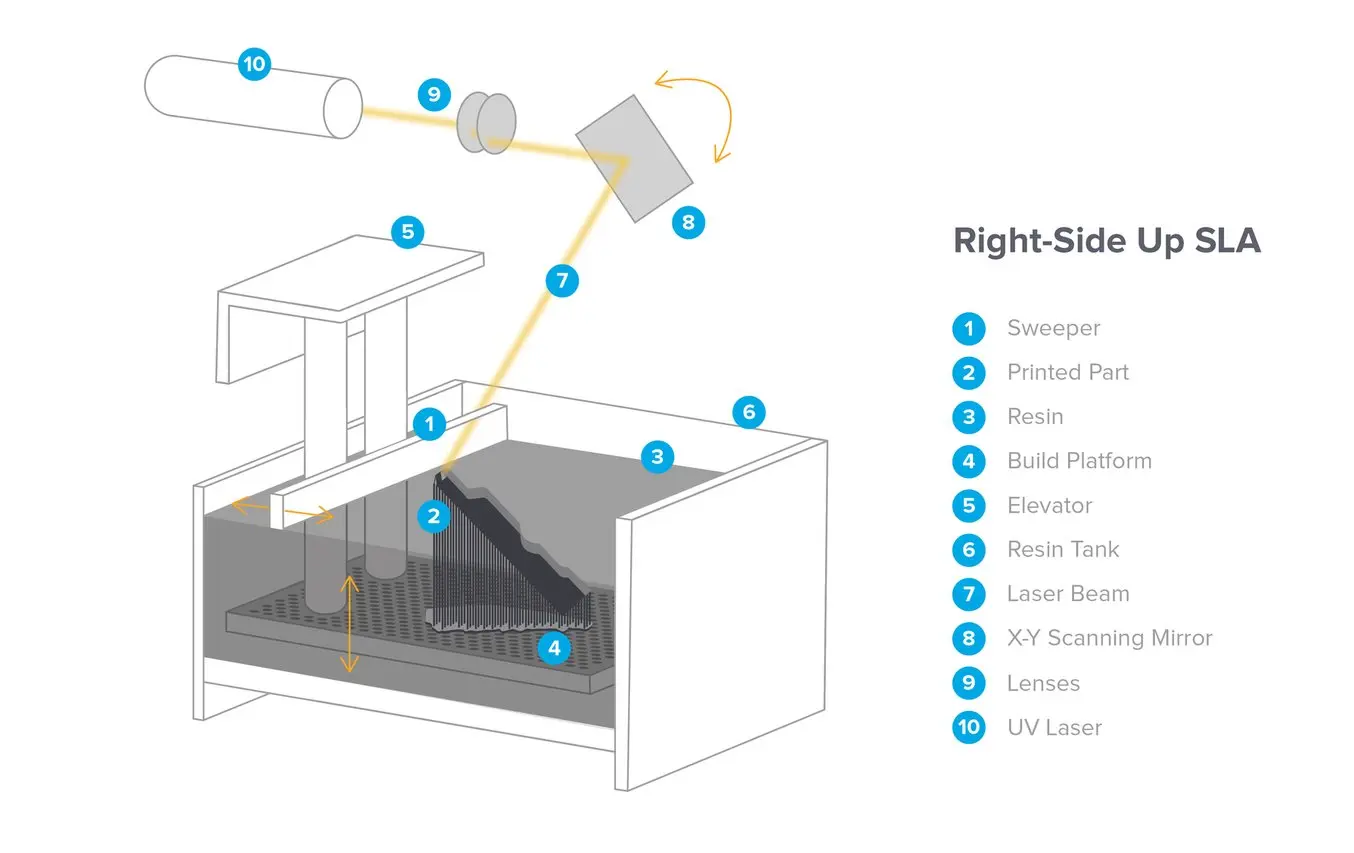

The first stereolithography printers used right-side-up methods, which require a large resin tank. Due to the large setup, maintenance requirements, and material volume, right-side-up SLA requires a high initial investment and is expensive to run, so it is mostly found in industrial machines.

Right-side-up SLA is common in industrial machines.

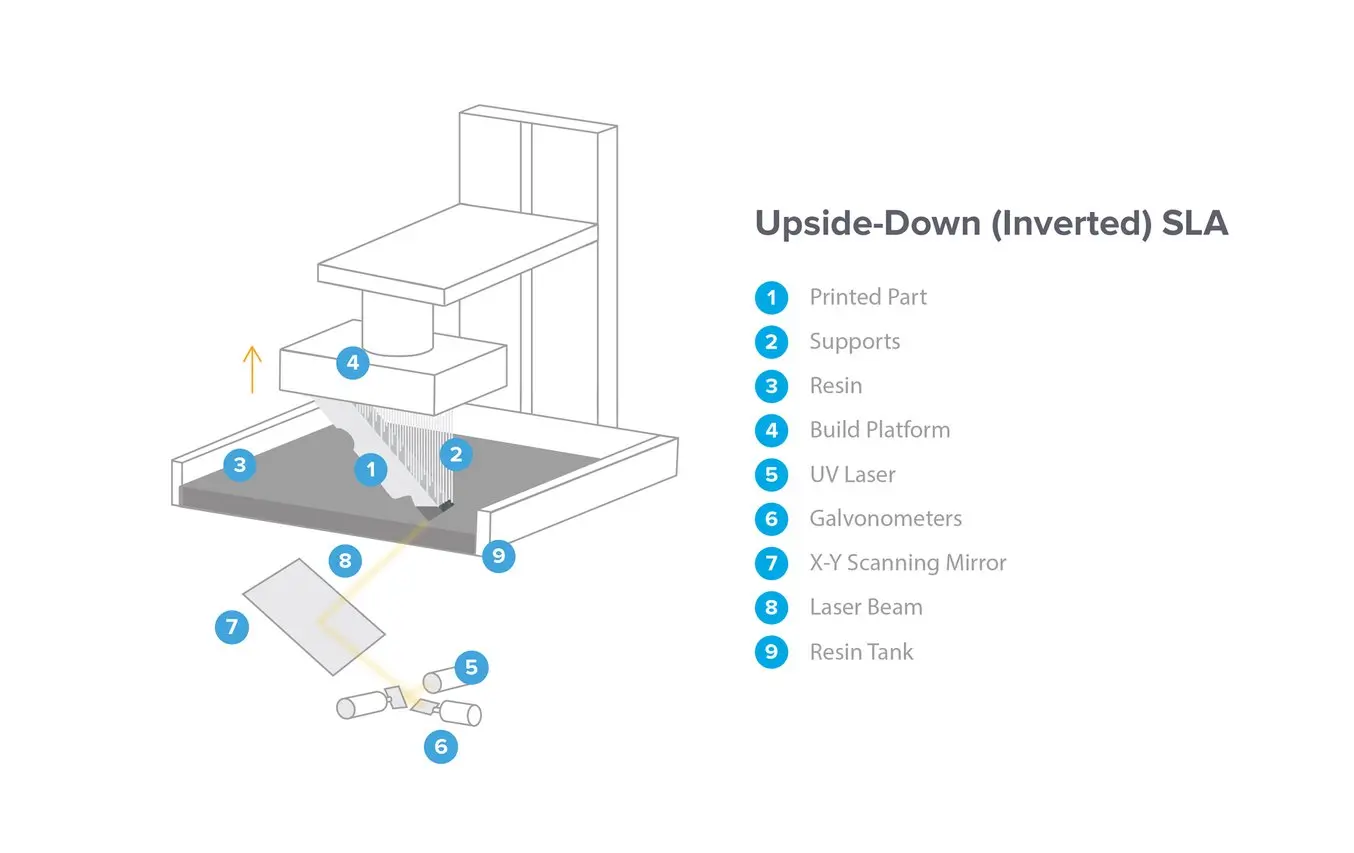

The advent of inverted SLA changed the game, since the upside-down method requires a much smaller resin tank compared to build volume. The creation of upside-down machines allowed stereolithography to move to the desktop, with a smaller footprint and much lower cost, making these highly accurate industrial machines accessible to far more businesses.

Because upside-down SLA, pioneered by Formlabs, requires a smaller resin tank than the right-side-up process, stereolithography 3D printing was able to move to the desktop.

The Future of Desktop Fabrication

At the beginning of 3D printing’s history, its benefits were limited to high-end uses for Fortune 1000 companies like Boeing and Ford. But that’s been changing for a while: now, you’re likely to find a professional 3D printer in a small design firm or even your dentist’s office.

Today, Formlabs is excited to be one of the companies driving innovation around stereolithography, from pushing for more accessible systems to developing exciting new materials, opening up new applications for 3D printing across industries and applications.

We’re excited about the future potential of professional 3D printing, and we’re going to keep placing our bets on accessible industrial technology, in hopes of increasing not just the number of machines and materials available on the market, but the number of people who can use them and the ways they can augment work for all kinds of companies.